We remember those who are deceased and those who are earthly present as they march in honour of the dignity of the human person and the experiences of what they have endured.

My family like so many others has a strong connection to war.

I knew my grandfather as having a deep love of the environment and everything living within it. I feel blessed to have a tree fern growing that was transplanted from my grandparent’s garden in Mayfield. It is well over 15 ft high, continues to grow, and is more than 30 years old. I look at it reminds me of the love that my grandparents had for each other, a love that would not have come about if not for World War II.

My grandfather Herbert O’Mullane was born in Frankfort, Indiana, and had lived in several towns in the USA before and during the Great Depression. I have strong memories of completing an assignment in primary school about the great depression and writing about my grandfather growing up in those difficult times. He recalled regular 4am visits to the bakery as an eight-year-old to see if there was any burnt bread that was going to be thrown out. His parents were without work for two years and were in desperate need of food. Sharing a bed with his parents and brother to stay warm because of no electricity. Walking along a train track in gifted shoes three sizes too big in the snow looking for pieces of cole that had fallen from the train. These experiences are burnt into my understanding of my grandfather and contribute to his apparent less is more philosophy.

When the family left for California, it took up to a year or so to arrive at their destination. They travelled through several states. My great grandfather was able to get some work to earn money for food and fuel until they got to the next town.

Poverty led to illness from lack of nutrition which left Herbert bedridden on and off for two years. The family was near starvation. My grandfather would say to my mother, "You can go without food for one day, even two days but, by three days that's the real critical time. You have to have food." Despite missed education, Herbert did manage to complete his schooling at LA High in 1940. He spent two six months enlistments before completing his final education in the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) which was staffed by US Army personnel, this enabled him to earn an income to support his family and rebuild his strength after previous years of serious illness.

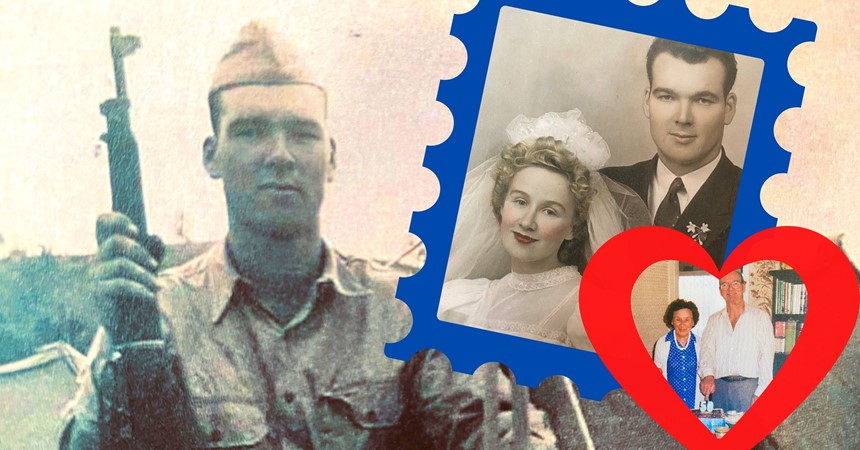

While Herbert did have a job at the time as a radio assembler, he enlisted in the US Army as a volunteer and was then sworn in aged 21 on 20 August 1941.

The year later, Hebert arrived in Australia after a six-week boat trip loaded with 8000 troops. After 10 months of training in Victoria and Queensland, Private First Class, Lance Corporal of 41 Division, Company D, landed in Port Moresby in December 1942. The main areas of operation for Herbert were, Milne Bay-Oro Bay and Buna in Australian Papua and New Guinea, Hollandia, Biak and Sansapur in Netherlands New Guinea, and Luzon in the Philippines. Herbert spent most of his time in combat as radio operator and was later promoted to Corporal leading sections of troops and reporting landings.

It was in 1944 on his return to his unit at Sansapur that Hebert discovered that he could take leave in either Brisbane or Sydney. He asked for Sydney but was advised that the places on the plane were full so asked for any other city and was offered Newcastle. Getting to Newcastle was more involved as there were no direct flights. It required a flight from Sansapur to Port Moresby then to Brisbane and a train to Newcastle. When he arrived at Newcastle railway station, he reported to the US Army liaison officer and was required to stay at the Red Cross hostel just off Hunter Street. Having explored the area he found a pharmacy opposite the Post Office in Hunter Street which he assumed was like a US drug store, selling just about everything. The pharmacy was attended by a young man, Brian Horton (later Marist Brother Cyrillus) who struck up a conversation and invited Herbert to come to dinner at his family home.

Herbert arrived at 16 Scott St Newcastle at 6.00pm the following evening and was introduced to the Horton family which included one Mary Horton (my grandmother). I have an angelic vision of my grandmother as my grandfather described his first encounter of Mary walking down the stairs. Slim, blond just over 5 feet tall, the most attractive person he had ever seen. He immediately thought, 'this is the girl I want to be with for the rest of my life!' During his stay in Newcastle, Herbert spent every opportunity at Scott St, walking Mary home from her workplace and attending mass with the family.

Herbert wanted to marry Mary, but she said she hardly knew him. Herbert also realised that Mary was Catholic and though both his grandfathers were Catholic, his grandmothers were staunch Protestants. He had been brought up, by his mother as an Evangelical Lutheran, though he had occasionally attended Catholic Churches partly out of curiosity.

When the time came to return to New Guinea, Herbert made two significant decisions: to write to Mary at least once a day and to convert to Catholicism. Before Herbert departed Newcastle, he bought a few hundred stamps and some literature on Catholicism from the Sacred Heart Cathedral.

On his return to New Guinea Herbert started discussing Catholic beliefs with Catholic friends from his unit. He was introduced to the Catholic Chaplain who eventually baptised him as a Catholic (though he was already baptised a Lutheran at birth) at Sansapur, Netherlands New Guinea in 1944, with his Catholic sergeant as a sponsor. The baptism certificate was registered at San Francisco where the chaplains had their administrative office, this was to avoid naming combat areas in case documents were obtained by the enemy.

Having spent 81 days in direct combat in the Philippines, Herbert was granted 30 days' leave in Newcastle. He had sent letters every day to Mary seeking her hand in marriage and she had agreed to the proposal. Herbert O’Mullane married Mary Horton on the morning of 12 May 1945 at St Mary’s Star of the Sea, the Banns of Marriage were read out two Sundays before the date as required by Canon Law. A wedding breakfast was celebrated to break the fast after which Herbert and Mary caught the Newcastle Flyer express train to Sydney, staying at a hotel near St Patrick’s Catholic Church.

When the leave was over, and Herbert was required to return to the Philippines there were a number of transport setbacks but he was required to report to the US Army headquarters near Wentworth Park every day. According to Herbert, Mary’s time was spent praying and attending mass at St Patrick’s.

When Herbert returned to the Philippines in July 1945 there was a different feel and a major change to the landscape and attitudes. There was little action and things had really quietened. In early August the unit was advised that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima followed by one at Nagasaki. Immediately members of the unit were receiving orders to return to the USA with an option of discharge or applying for transfer. Herbert requested discharge in Australia which was eventually approved.

Herbert and Mary had four children in the following years and purchased their first house in Mayfield. While Hebert had a desire to move back to the USA as he had not seen his family for such a long time, this was short-lived because Mary was so homesick.

Growing up we would regularly attend mass with my grandparents at Christ the King, Mayfield West. Both grandparents had a deep faith and 6ft Herbert would do anything for his little Mary. It was a love that lasted and when Mary passed away, Herbert could not live without her and died heartbroken only eight months later.

This account only provides a fraction of the experiences by grandfather encountered during his time in WWII. Growing up, when he did speak about his time during the war, he did through the eyes of love for those who had lost life. The scars which would have haunted him were not visible to his family, his focus was on life.

A special thanks to my uncle Michael O’Mullane who wrote Soldier in the Pacific. World War II Experiences of Corporal Herbert Warren O’Mullane. This was written in 2020 in memory of his father’s 100th Anniversary of his birth. This information along with the stories I have grown up with have kept this love story alive.