It was a coincidence this year that Ash Wednesday also fell on Valentine’s Day. The 14th of February is a close friend’s birthday, so several of us gathered to share a meal to celebrate another year of their life. It was during dinner that I took the opportunity to explain the significance of the day from a Catholic perspective to my friends who are unfamiliar with Lent. As the conversation flowed, we also spoke about Ramadan, discussing it being a similar time of the year and the comparisons with Catholic practices during Lent, namely fasting and almsgiving. One of my friends asked the question of why different cultures also participate in Carnival around the same time of the year, this led me to further explore its historical roots and its connection to Lent.

Carnival is celebrated in many ways throughout the world. If we think about Carnivals, images of colours, lights, music, dancing, parades and entertainment come to mind. If we think about Carnivals in places like Brazil or New Orleans, images of women with little clothing, who are highly decorated with head dresses, feathers and sequins cross our mind.

The origins of Carnival are said to come from ancient Egypt and Rome. In Egypt, as far back as 4000 BC, the festival was said to be celebrated as the seasons transitioned from winter to spring. The Romans engaged in parties with excessive drinking to celebrate Bacchus, the god of wine, freedom, intoxication and ecstasy.

The word Carnival is said to come from the Late Latin (the period from the 3rd to the 6th centuries) expression carne levare, which means "remove meat” or "farewell to meat". The word carne may also be translated as flesh, producing "a farewell to the flesh".

In the Middle Ages, Carnival referred to a period following the Epiphany which concluded on Shrove Tuesday. It represented a last period of feasting and celebration before the spiritual rigors of Lent. Pope Gregory the Great (590–604) decided that fasting would start on Ash Wednesday. The whole Carnival event was set before the fasting, to set a clear division between celebrations and penitence.

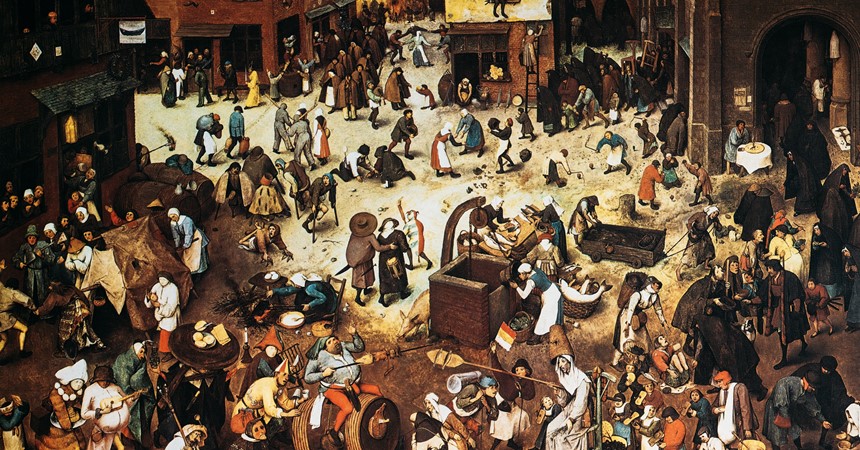

In the artwork The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, (1559) artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569) a loyal Catholic, depicts the clear division between a time of indulgence and a time of fasting.

‘In the foreground is the battle itself: the two opponents, Carnival and Lent, pulled and pushed and accompanied by supporters, are about to meet. Carnival is seated on a large beer barrel and Lent is opposite him seated on a shallow pull cart.’

‘Carnival is a fat butcher, with his pouch of knives, straddling a beer barrel on a blue sled. A pork chop is attached to the front of the barrel, and a cooking pot serves as a stirrup. His weapon is a rotisserie carrying the head of a suckling pig, poultry and sausages. Two men pull his sled. One of them waves a red-gold-white flag, the then typical carnival colours. Carnival's followers form a procession of figures wearing masks, bizarre headgear and household objects as props or improvised musical instruments, in a reversal of the normal order. The followers are provided with wafers and cakes. In the foreground are bones, eggshells, and playing cards.’

‘Lent is a thin woman, seated on a hard three-legged chair, and armed with a baker's spatula called a peel, on which lie two herring. She is surrounded by pretzels, fish, fasting breads, mussels, and onions, all typically consumed during Lent. Lent’s cart is laboriously drawn by a monk and a nun. Her entourage consists of children, who, like Lent, have the ash cross of Ash Wednesday on their foreheads. They make noise with clappers. A church minister accompanies the children, carrying a bucket with a holy water brush and a bag for donations, which include dry rolls, pretzels and shoes.’[1]

The transition to Lent especially in an Australian context is not as extreme as the one Pieter Bruegel the Elder depicts in his artwork. We still carry the tradition of having pancakes on Shrove Tuesday, which is also known as Mardi Gras, Fat Tuesday, Pancake Tuesday or the last day of Shrovetide, depending on where you live in the world. Shrove comes from the word shrive meaning absolution following confession and eating pancakes on this day represents the feast or indulgence before the 40 days Lenten fast. Many cultures around the world still come together to mark this time in the liturgical calendar through carnival activities in preparation for Lent.

The 40 days of Lent remind us of Jesus being tempted in the desert for 40 days, the Israelites wandering in the desert for 40 years. The 40 days and nights of rain before the Noahic covenant was established. The 40 weeks it takes to grow a new life. It is a period of awakening, self-reflection and transformation, metamorphosis occurs as we journey through Lent to Easter.

There is much we can contemplate when reflecting on the concept of a fight between two ways of existing, either feast or fast, we can also consider injustices of inequality in our world. Then God said, 'See, I am setting a plumb line in the midst of my people.' ( Amos 7:8)

During the season of Lent, we are called to look deeply at the human condition, just as Jesus, the Son of God, experienced. We are reminded during this time of hardship, suffering, and ultimately dying, that we must stretch ourselves. We must pray and fast from whatever is taking hold of the fullness of life. This time calls for personal reflection and encourages us to look out with missionary eyes, to intentionally give to those in need.

It is part of the Christian mission to reflect on the Paschal Mystery. This assists us to understand questions about the meaning of life, the realities of suffering and what it means to rise above to new life and resurrection.

This Lent we are invited to turn to God dwelling within us and consider how we can reach out to those people in our local, national, and global communities to make a difference, to adjust the unequal scales of justice so we can combat the fight between the everyday Carnival and Lent.

You are welcome to join the Lenten Reflection group at the Diocesan Library (corner of Tudor and Parry St) commencing the first Friday of Lent, 23 February from 9am-10am. Links: Registration or access the Lenten Reflection.

Image: The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, (1559) artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Shuttershock

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Fight_Between_Carnival_and_Lent

Follow mnnews.today on Facebook.