Fr Therry’s interest in Australia, aroused by the transportation of Irish convicts and the publicity surrounding the forced return in 1818 of Fr Flynn, came to the notice of the authorities when they were looking to send two Roman Catholic chaplains to New South Wales. Fr Therry, recommended by his bishop, Dr Murphy, ‘as a capable, zealous and valuable young man’, sailed from Cork under senior priest Fr Philip Connolly on board the ship ‘Janus’, which also carried more than one hundred prisoners. They arrived in Sydney in May 1820, authorised by both church and state.

Fr Therry described his life in Australia for the next forty-four years as 'one of incessant labour very often accompanied by painful anxiety'. Popular, energetic and restless, he appreciated from the beginning the delicacy of his role. He had to be at once a farseeing pastor making up for years of neglect, a conscientious official of an autocratic British colonial system, and a pragmatic Irish supporter of the democratic freedoms. Though respectful of authority and grateful for co-operation, he was impatient of any curtailment of what he considered his own legal or social rights as a Catholic priest in a situation governed by extraordinary circumstances. [Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol. 2 (MUP) 1967]

Although Fr Therry was mindful of the authority of the British colonial system, he worked tirelessly to improve the conditions of his flock and the disadvantaged. This of course often met with opposition and on one such occasion it led to his official status being withdrawn.

The British government decided on a major religious adjustment to ensure the stability, and increase the influence, of the state Church and Fr Therry had to fight for permission to carry out the vital services of his ministry. With the creation of the Church and School Corporation in 1825, the Church of England, under the leadership of Archdeacon Thomas Scott, was overwhelmingly favoured and although Fr Therry had established friendships and contacts with non-Catholics, he now became prominent in a possible opposition party. In an article printed in the Sydney Gazette on 14 June 1825, Fr Therry was misquoted in reference to ‘the other Revd Gentlemen of the Establishment’ which eventually resulted in Governor Darling removing his official status as Catholic Chaplain and withdrawing his salary. He was offered 300 pounds to leave the colony but refused to go and continued what he knew was his God-given work.

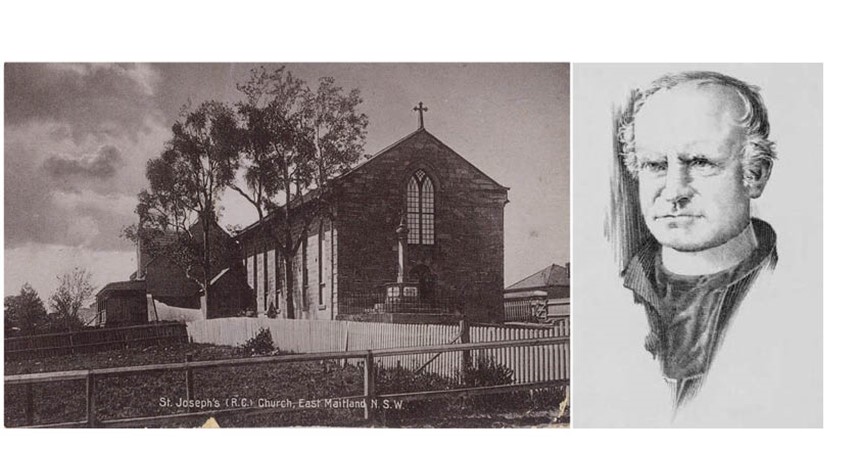

From that time until his reinstatement in 1837 Fr Therry continued his work as before but was forced to be more cautious and sometimes even secretive, as there were many who, because of their animosity, did everything they could to hinder him. He did not always advertise his movements. He carried on ministering to his people and deprived of his pension of 150 pounds per year relied upon their support for day to day living. He travelled whenever he was summoned, to Wollongong, Goulburn, Maitland, Bathurst and Newcastle.

The following extract from Dean Kenny’s “Progress of Catholicity in Australia” gives us an insight into the character of Fr Therry.

‘….the Rev. Father was prohibited from visiting the sick in the hospitals and infirmaries – when he could not administer to them the consolations of our Holy Religion. To show the fortitude and address of this apostolic man, whilst under ban, he went to visit a dying man at one of the hospitals. He was stopped by the guard when about to enter. Father Therry said to him, “the salvation of his man depends on my ministration; which is your first duty?” The guard, recognizing the right of the man of God, lowered his arms and permitted him to pass. At another time he was going into the infirmary to attend a sick person, when the doorkeeper told him to stop until he ascertained from the attendant surgeon whether he could be admitted. Whilst he was away, Father Therry, who knew all the passages of the place, entered, gave the sick person consolation, and when returning met the official, who told him he could not be admitted. Many of the petty officials were very insolent to Father Therry and his flock, taking advantage of the circumstances. It was permitted to have divine service in the old Court House, a large building, now a public school in Castlereagh Street, but because their pastor was not recognised by the Government, the door was locked against them. But in defiance of such insolence the door was forced open. It is said Mr Wentworth, the lawyer, was consulted as to the steps the Catholic ought to take to secure the Court House for divine service, as they had as good a right as others to use it for that purpose. “What will you do?” said Wentworth. “Why, take a crowbar and break the door open; and if they take you to court, send for me, and I’ll defend you”.’

In 1932 Dan Ryan, a highly respected and reliable Maitland resident who did much research into the early history of Catholicity in the Hunter Valley, wrote “Father Therry must have been a frequent visitor to Maitland, as he was held in reverence by the old settlers, and his memory was a treasured one with their children.”

Early documentary evidence of Fr Therry’s presence in the Maitland area is from a letter which appeared in The Australian on November 2, 1827. The letter was dated October 29, 1827 and the writer was from Newcastle.

‘The Reverend J. J. Therry has been here during the last fortnight. He has twice celebrated Mass at Newcastle (on Sunday and Sunday week) and has made in the interval a tour into the interior. His arrival has been hailed by all good Catholics with enthusiasm. The Venerable Archdeacon (C. of E.) has also made his appearance amongst us. He came here on Saturday last overland from Port Stephens, and set out today for Wallis Plains. He proposes, I believe, returning to Sydney by land conveyance.’

As reported previously, this was not Fr Therry’s first visit to Newcastle and the interior.

To be continued …

This is part of a series about the history of the church in the Maitland area:

Read Part One – The Catholic Church in Maitland

Read Part Three – Who followed Fr Therry to Maitland?

Read Part Four – Ship wrecks and close calls with cannibals